A Chat with Charles: Steps to Reduce Energy Use in Retail Stores

A Chat with Charles: Steps to Reduce Energy Use in Retail Stores

Charles R. Zimmerman recently retired as the Vice President of Design and Construction for the International Division of Walmart Stores, Inc. and is now owner of Global VE, a consulting firm focused on worldwide value engineering and capital efficiency. Retailers who want to reduce energy intensity in their stores can learn from Mr. Zimmerman’s many experiences spearheading sustainable building initiatives since 1989.

This month, Charles chats with Current about proven approaches to energy management and why many merchants remain wary of the “Amazon effect.”

Current: Looking back, how has retail store energy management changed over the last 10 years?

Charles: It’s certainly a more holistic approach in that retailers are looking at every cost reduction opportunity, from lighting to refrigeration to heating, ventilation and air conditioning. These operating expenses can be substantial—McKinsey & Company found energy accounts for between 4% and 9% of in-store operating costs, depending on the retail format. Many merchants are focused on making incremental improvements to equipment, infrastructure, policies and procedures that can add up to measurable savings. At the same time, it’s become much easier to leverage lighting and building controls as part of your management strategy. Today’s web-based systems let you monitor and troubleshoot from anywhere, anytime, so you can make changes from your device or smartphone, which is a level of convenience and responsiveness that simply didn’t exist before. Somewhat surprisingly, commercial business consumes 8% more electricity a year than the industrial sector, according to the EPA, which helps explain why so many retailers have committed to reducing energy demands during operating hours especially.

You’ve personally evaluated an array of technologies and approaches aimed at reducing energy use in stores. What stands out to you?

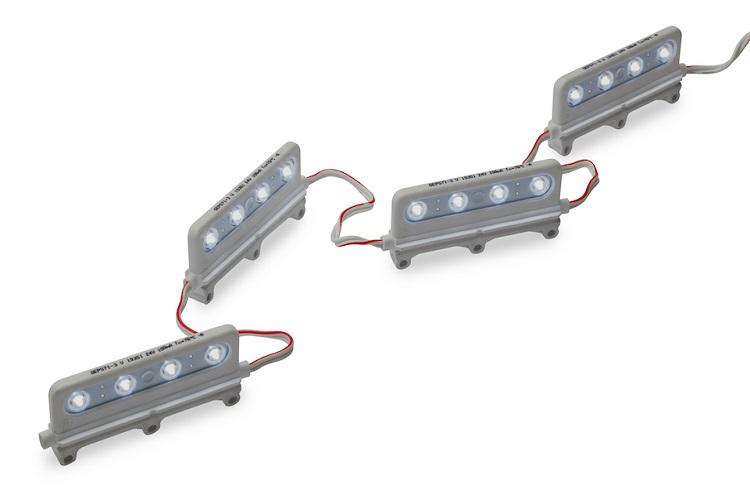

I think any operations director will tell you LED lighting has been a focal point for quite a while. The thing is, you didn’t see LED on the general sales floor ten years ago because it didn’t make economic sense. What you had—and what you still have in many stores—are fluorescent lamps that are rather inexpensive, relatively efficient and simple for anyone to replace, so LED was in parking lots, freezer cases and signs at first, but that might account for only 5% of the total lighting energy in a building, meaning the real opportunity was still out there.

I remember plotting on a time horizon when we thought LED would be viable for the sales floor, and we arrived at 2020, which I can now say we missed by about five years because the technology advanced beyond initial expectations—even the experts missed how rapidly LED evolved in terms of quality and efficacy. Since then, I’ve documented energy savings from 40% to 60% where LED replaced fluorescent lighting on the sales floor. It’s easy to point to that utility bill every month and know exactly the impact it’s having.

Also realize we’ve reached a point where LED is largely optimized, and costs have flattened out, so there will be slight improvements moving forward but not the big changes we’re accustomed to. Even a few years ago you could justify the cost of replacing LED with LED in certain situations because the technology had come that far that fast.

Around 2015 you started to see stores made up exclusively of LED, and LED is the sole spec for all new construction in a lot of cases now. It’s more efficient and versatile, it lasts longer, and it’s just an overall better quality of light. A lot has changed in a decade, but lighting’s evolution has been quite dramatic.

What are other ways you’ve effectively curbed building energy use beyond lighting?

In refrigeration there’s a huge opportunity to put doors on open cases, despite resistance from much of the market. After years of studying the problem, I had a saying, “an open door is like an open checkbook.” In horizontal cases the cold air settles until someone reaches in, but in vertical cases gravity alone is constantly drawing that air out.

In my experience, putting doors on horizontal cases reduced energy demands by 50% and in vertical cases, it was 70%, which is significant no matter what protests management might have had about putting a pane of glass between shoppers and fast movers like milk and eggs.

Of course, the argument is customers don’t want to be inconvenienced, but ask yourself, how is a door a barrier to bologna but not ice cream? The number one customer complaint in supermarkets is that it’s “too cold” and all those open cases have a lot to do with it.

In fact, I’d argue doors are not an annoyance whatsoever. We’d ask shoppers about them and they were shocked—“I didn’t even notice, I was just in a hurry to get going” is what we heard. In some stores we even saw an uplift in fresh meat sales because the customer perceived the product as fresher, which is true because it helps maintain a longer shelf life.

Anytime you can reduce your overhead and improve the shopping experience, that’s a win-win.

With such clear savings potential, why aren’t more retailers racing to invest in energy-efficient improvements?

I think for many it’s a matter of not doing anything to negatively affect sales. They know they can save, but they also know it requires a certain stamina and discipline not every retailer is ready to commit to. Twenty years ago, the industry was mainly concerned with first cost, and over time that pendulum swung to a wider view of asset lifecycle spending, but now the pendulum is swinging back, and it’s fair to say the “Amazon effect” is driving it.

Merchants have become very first-cost focused once again because, what if this doesn’t work? They don’t want to discuss long-term payback initiatives when they aren’t certain they’ll be operating the store in three years, or if that 50,000-square-foot supermarket is going to be mostly dedicated to distribution five years from now. The pushback is stronger because the future is uncertain, and that’s why I’m challenging leaders to really examine if you’re making the right decision.

Particularly where the project payback window is less than three years, the cost of waiting can put your business at a competitive disadvantage that makes the “Amazon effect” secondary. These pendulum swings tend to be short lived, and as clarity returns to the market, your CFO is sure to ask why energy spending is suddenly outpacing the competition.

What would you say to retailers who cite cost as the biggest barrier to making stores more energy efficient?

If you can’t afford to replace your lights, start by looking at options for not keeping them on, or at least not on at 100% brightness, all the time. A lot of people think lighting controls cost thousands of dollars to commission, but a basic system that can dim and operate your lights on a schedule might total several hundred dollars, which could easily be your first month’s savings.

In my experience, controls are a fraction of the cost of a new lighting installation, and the ROI is something you can capture right out of the gate. Think about a 24-hour grocery store that operates its lights at full brightness at 10:00 p.m. That lighting is harsh to shoppers walking in at night, so why not start to dim the lights based on sundown for that location? That’s five hours or more of savings you could be enjoying, while making customers feel more comfortable in your store. The reality is you don’t have to add a sensor to every fixture to take advantage of lighting controls.

Another gamechanger is applying variable frequency drives (VFDs) to compressors and fans, which allow HVAC and refrigeration equipment to operate in that bandwidth between “on” and “off.” By controlling the motor’s speed over a narrow range, it’s possible to reduce energy demands by 30 percent or more and extend the life of existing equipment. Demand-based control is energy efficient, and your payback can range from just six months to two years, typically.

What parting advice would you offer fellow design and construction professionals tasked with cutting energy use in retail stores?

Having aggressive, publicly stated energy goals is important to setting the tone for your company from the top down, which can spur action, open doors and make everything easier as you coordinate with internal players and outside partners.

Also, it’s going to take passionate directors and energy teams to be compelling storytellers. I’ll hear, “My CFO won’t let me do X, Y and Z …” but have you clearly explained the payback and made a compelling case? Those discussions need to be taking place right now, and you need savvy partners backed by data to help you make an effective argument.

Finally, take time to listen no matter where the ideas come from, even if that’s a person working out of their garage. During my career, if we couldn’t look through their data and see an obvious flaw, we’d invite them in, share our plans and encourage them to go back and show us how their solution was a fit. If we couldn’t figure out how it wouldn’t work, we’d let them trial it in a store, whether that was a row of lights or a single RTU.

There will always be an element of trial and error, but you can minimize that risk by taking a close look at what others have already done to run the traps. It’s a learning process, but the rewards can be significant for stores that adopt a culture of saving energy at every opportunity.

We hope you enjoyed our chat. There’s even more in store next month as Charles explains why the freezer aisle is the next stop for smart retail IoT.

See how leading retailers are leveraging LED lighting and controls to create amazing possibilities.